WHERE DO YOU STOP?

(A Novel)

By

ERIC KRAFT

“A magical, funny, healing journey that features familiar and unusual memories . . . without lapsing into mere nostalgia.”

Malcolm Jones Jr., Newsweek

Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night over the Rhône (detail, 1888)

“The title of this sly and extremely funny book is also the title of a paper that Peter is assigned by his science teacher, the luscious, leggy Miss Rheingold. We — and Peter — learn quite a bit about Miss Rheingold, although nowhere near as much as Peter would like. We also learn about epistemology; the boundaries of the self; the building of backyard lighthouses; terrazzo floors; Chinese Checkers; American education; the restricted vision of children (and their parents); and the design of such exquisitely intricate gadgets as the phonograph, the scanning tunneling microscope, the universe, and the novel. . . .

Mr. Kraft is his own man, with his own somewhat loopy agenda. He writes an elegant, supple, uncommonly precise prose that glides, silk-smooth, from pathos to parody, from slapstick to sentiment, from the mysteries of moonlight on Bolotomy Bay to the mysteries of particle physics. Toward the end of [this] book, he creates several scenes involving Peter and Ariane, the sultry older sister of Peter’s best friend, Raskol. Each vignette is a perfectly balanced blend of slightly edgy comedy and shrewd observation; and each is also extraordinarily sexy. The unattainable Ariane is breathtakingly desirable, and Peter’s desire — the awful, ecstatic ache of preadolescence — is rendered so artfully that it becomes almost palpable.”

Walter Satterthwaite,

The New York Times Book Review

“The giddy excitement of expanding scientific consciousness is coupled with the awakening of sexual desires in this goofy and thoroughly enjoyable novel. . . . You won’t want this charming little exercise in learned whimsy to end.”

Timothy Hunter, The Cleveland Plain Dealer

A Sample

(From Chapter 3)

WHEN I FOUND MYSELF BORED, when I didn’t know what to do with myself, when I was a little on edge and needed to find or devise a way to relax, or even when I was just looking for a way to pass the time, I sought inspiration in junk.

Most of the time, I found it there. The ready availability of intriguing materials is, I think, a spur to creation more often than the arrogance of artists allows us to admit. Fortunately for me, I lived in a family where there was plenty of intriguing stuff around. They regarded any supposedly useless thing with the attitude that its true, deep, hidden, or overlooked utility would be revealed—eventually. This attitude was summed up in the words they muttered when they tossed the thing into a corner of the cellar instead of tossing it into a trash can: “Never can tell—might come in handy someday.” For me, these things already had their uses, since they were fodder for my browsing.

I have said it before: so much depends on chance. There I was, down in the cellar, poking around in the junk, when I came upon something intriguing: the remains of an old windup record player. Thank goodness, it had no amplifying horn, no pickup arm, no needles. If it had, I would never have seen it as raw material; I would have seen it as a record player, and I would have been blinded by that perception of it. I might have tried to fix it, and I might have filled the afternoon with the effort, but I would probably have failed and emerged from the experience frustrated, diminished by failure, possibly scarred for life. Instead, thanks to the providence that had dictated the evisceration and amputation of certain record-playing essentials, I saw only an engine, just something that would make something else rotate. Its life as a record player was over, but there was a vital spark in the old gadget yet. All I had to do was discover its true, deep, hidden, or overlooked utility.

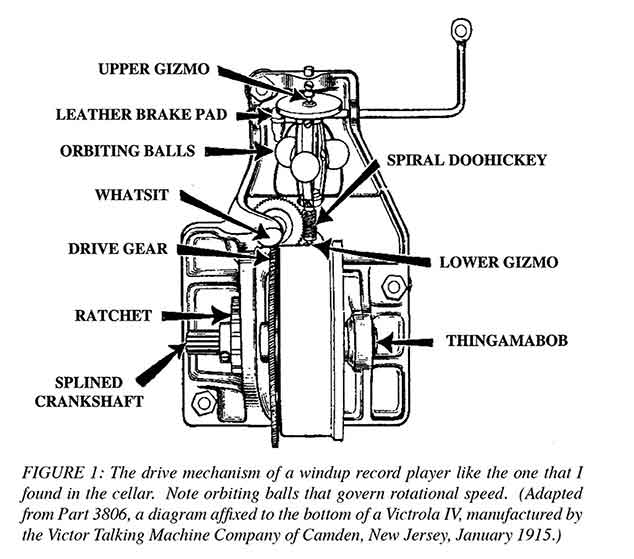

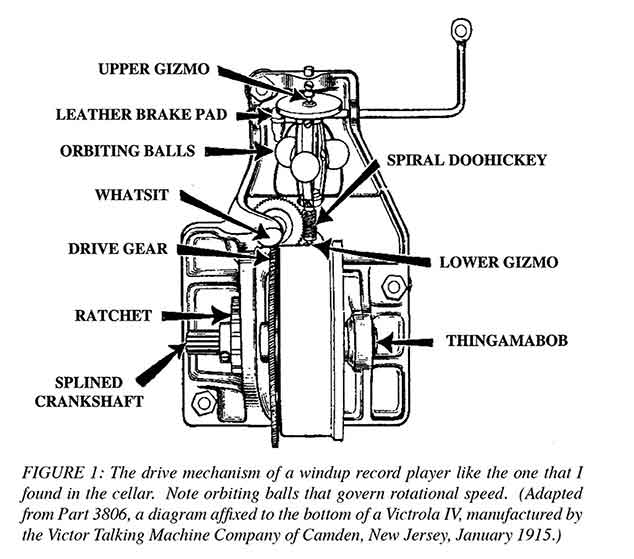

The thing as I found it was, essentially, this: a motor driven by a spring that the operator wound with a large crank (see Figure 1). The motor was mounted vertically inside an oak box, with the shaft emerging from the top of the box. Mounted on the end of the shaft, outside the box, was a platter, covered with green felt. The record was supposed to spin on this platter, of course. Mounted farther down the shaft, inside the box, was an intriguing trio of metal balls. The adjustable orbiting balls acted as a governor, a limiting device. Their original purpose had been to allow the operator to keep the platter spinning at the 78 rpm of old shellac records, so the range of adjustment was kept short, just a narrow band at the center of the machine’s possible range of speeds. The original purpose didn’t interest me, though. I wanted to see the machine spin at its extremes, so I began dismantling the governor.

By removing the adjusting screw entirely, I could make the platter spin much faster than it was ever intended to spin, and by doing away with the trio of balls I could make it spin faster still, quickly enough to catapult small objects from its rim. I tried this for a while, shooting things across the cellar and marking record distances on the floor, but I quickly reached the catapult’s practical limits, and the record player vibrated so violently that it seemed likely to shake itself to death, so I gave that up.

More intriguing was the opposite extreme. With longer screws I could slow the machine down. When I’d inserted the longest screw that would fit, driving the top collar down against the bottom one, I thought for a moment that I’d slowed it as much as could be done, but a little thinking showed me the next step: longer arms, bigger balls. It was the work of a happy hour to attach three dowels to the platter, each with a rubber ball at its far end. . The whole arrangement reminded me of the electrified model of the solar system kept in a glass case in the hallway of the oldest of the elementary schools in town. At the center, symbolizing the sun, was a naked light bulb. That, I saw, was what my gadget needed—a light.

I thought of trying a small table lamp, but my mother spotted me sneaking it out of the living room, so I had to settle for a flashlight. I taped the flashlight to the platter, wound the motor, and released the brake. Watching the spot of light moving around the walls of the darkened cellar, I realized that I had here the essentials of a lighthouse. I had wanted a lighthouse of my own for years. Now I was halfway there. I had the mechanism. All I needed was the shell, the housing, the lighthouse equivalent of the record player’s cabinet. That couldn’t be hard to come up with. Next to what I had already accomplished, it ought to be a snap. I didn’t see any reason why, with some help, I couldn’t build a lighthouse in the back yard in a couple of days. Of course, I would need my father’s permission. . . .

It would be best, I reasoned, not to announce my intention to build a lighthouse, o claim that I had something else in mind, something more modest. I asked permission to build a shack.

“A shack?” said my father.

From something in his voice, I realized that I had chosen the wrong word.

“Well,” I said, “not a shack, a hut.”

“A hut?”

“A fort,” I tried.

“A fort? What kind of fort?”

“More like a clubhouse,” I said.

“Oh!” he said. “A clubhouse. Sure. Why not?” . . .

I suspect that my father expected me to build, no matter what I called it, an eyesore, because he allowed me to build it only if I built it where it would be hidden by a grove of bamboo.

|

| |

Scroll down for another sample.

“It’s an enchanting comic meditation on the quirkiness of memory and the joys of daydreaming. At its most ambitious moments, it’s nothing less than an attempt to comprehend the nature of the universe itself.”

Michael Upchurch, The Seattle Times & Post-Intelligencer

Another Sample

(From Chapter 12)

MISS RHEINGOLD showed us a movie called Quanto the Minimum. It was developed, or at least sponsored, by the telephone company, and it featured a tiny cartoon character, Quanto the Minimum himself, who explored the constitution of matter as it was then understood.

As I recall, Quanto was an impish sort, sarcastic and even a bit nasty. He seemed always to be telling us, the captive audience, how stupid or ignorant we were. This abuse started right off the bat, when Quanto stood with his little hands on his cartoon hips and said right at us, “Hey, kids, I’ll bet you think you’re really something, don’t you? Ya-ha-ha! Well, get this—you’re really mostly nothing! Just wait till I get through here. You’ll find out that you’re mostly empty space. Ya-ha-ha! Come on! Come on along with me! I’ll take you on a remarkable voyage of discovery—from the farthest reaches of the universe to the tiniest heart of the tiniest atom—from the vastness of your ignorance to the tiniest little twinkling photon of enlightenment, which is really about all I can realistically expect to pass on to you with the budget they’ve given me to work with. So hang on! You’re in for some surprises. You’re about to find out that most of everything is nothing.”

Quanto did take us on a remarkable voyage, as he promised, but he was a difficult guide to follow because his style, like Miss Rheingold’s, was discontinuity. He jumped from one topic to another with no more transition than saying, “Wow! That was really something. Aren’t you excited? I am. I’m really excited!” Then, foom, off he’d go. He seemed to whiz right off the screen and rocket through a radioactive blue miasma for a couple of seconds, eventually reappearing in another location, calmer, a little worn out, breathing heavily, his snazzy red outfit torn here and there, to tackle the next topic. “Whew!” he might say. “That was quite a ride. Where are we? Ah! Alamogordo. Wait till you see this.”

We saw many things, a fascinating jumble: an atomic bomb blast flipping battleships like toys in a tub, solar flares lashing out like the whip my favorite movie cowboy carried, a Tinkertoy lattice that represented the molecular structure of some crystal or other and made chemistry look like lots of fun, and more. We learned a word that all of us went around using whenever we got half a chance since it was such a pleasure to say. It began with a funny buzzing, hissing, and shushing, generated a lot of saliva along the way, and its ultimate syllable made my mouth a cavernous space in which a howl resounded. This wonderful word was Zwischenraum, the word Quanto used for the empty space that is most of everything, the nothing that permeates and separates it all.

Among all the marvels in Quanto the Minimum, however, the universal favorite was a demonstration of the mousetrap model of a fission reaction. In this demonstration, a Ping-Pong table was covered with mousetraps, densely packed, but set at angles to one another, so that the model wouldn’t seem to be regularizing matter too artificially. All of the mousetraps were cocked and ready to spring, and resting on the wire bail of each was a Ping-Pong ball. An announcer appeared at the side of the Ping-Pong table. Quanto leaped onto the screen, said, “Keep your eye on this guy,” and leaped off, laughing.

The announcer waved his hand toward the Ping-Pong table, taking in its entire magnificent array of cocked traps and ready balls, and said in defiance of all logic, “This is Uranium 235.”

Then he went on to explain some things he seemed no clearer about than we were. He seemed to keep losing the distinction between the Ping-Pong ball he was holding as the Ping-Pong ball it actually was and the neutron it was meant to represent. Whenever he said that a neutron was used to bombard the Uranium 235 he made a dart-throwing motion with his hand, suggesting that the bombarding process was a heck of a lot like dart throwing, or at least that was the impression it left on most of us. When he had finished his taxing explanation, he said, “And this is the result,” and with coy insouciance tossed the ball into the array of traps.

Wow.

What resulted may or may not have been a good demonstration of what occurs during nuclear fission, but I am certain that I will never see a more vivid demonstration of an idea that my parents had tried to hammer into me back when I was just a kid, before I took up junk browsing as a pastime, whenever I became bored on rainy vacation days and pleaded with them to mitigate my boredom with a new model airplane kit or a dozen comic books. What they said—and this Ping-Pong ball experiment so spectacularly proved—was, “You don’t need model kits and comics to have fun. You can have a lot of fun with the things you find around the house if you just use a little imagination.” Definitely so, provided you could find a few dozen mousetraps and Ping-Pong balls.

The film ended. The fluorescent lights stuttered and flickered into life.

“We just have time for a few questions,” said Miss Rheingold.

Hands shot up all over the room. Miss Rheingold beamed with pleasure and satisfaction.

“Bill?” she said.

“Can you use just regular mousetraps, or do you have to get that model 235 they were using there in the movie?”

It took Miss Rheingold a moment to recognize what a depth of misunderstanding underlay this question. When she did, the corners of her mouth dropped. “Oh,” she said, or perhaps she just moaned. The bell rang.

|

| |

“A hilarious reminiscence of Peter’s pre-adolescent years, his awakening to sexual feelings, and other inchoate confusions.”

Bruce Allen, USA TODAY

A New York Times Notable Book of the Year (1992)

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

“Young Peter leads us on a merry investigation and exploration of his (and our) world, and, in the process, invests it with a great deal of warmth and humor and charm. . . . Mr. Kraft is a splendid, smart, funny, slyly sexy, and insightful writer.”

Michael Z. Jody, The East Hampton Star

Read complete reviews.

“Luminously intelligent fun.”

TIME

|