PASSIONATE SPECTATOR

(A Novel)

By

ERIC KRAFT

“Middle age, mortality, and the meaning of life: all are examined with the lightest touch imaginable. May it go on forever. ”

Kirkus Reviews

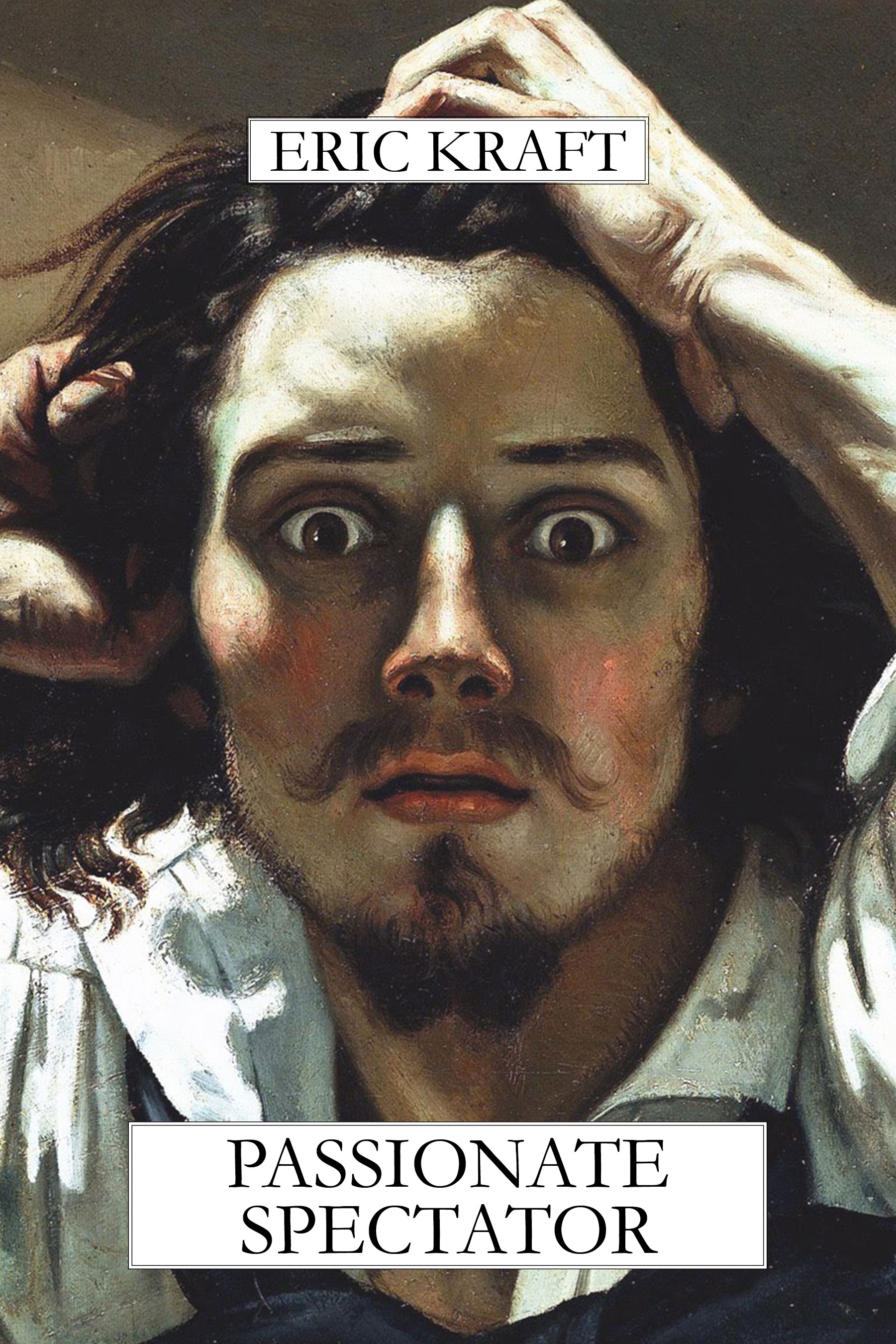

Cover image: Gustave Courbet, Le Désespéré (circa 1843, detail)

“Riotous fun. Another perfect book by an author whose works are, among other qualities, great intellectual fun.”

Bob Williams, The Compulsive Reader

“Kraft continues the charming and mischievously intellectual adventures of the eccentric writer Peter Leroy. He’s as ebullient, canny, and entertaining as ever.”

Donna Seaman, Booklist

A Sample

THE NEXT AFTERNOON found me lying on a chaise longue (which was costing me $10 for the day) on the beach (which was costing me nothing, if we don’t count the price of my room at the very reasonably priced Albatross hotel, which was $189 a day), scanning the sunbathers with my miniature binoculars (which had cost me $129.95). I concealed my scanning by draping a towel (provided free by the Albatross) over my head and the binoculars. Anyone who noticed me, would, I hoped, assume that I was meditating in some new fashion. Actually, I was looking for Corellians.

Earlier, in the morning, while Sheila and I were breakfasting on strawberries and cream on the terrace in front of the Albatross, I had read an article in the South Beach Buzz about these Corellians. They are followers of Massimo Corelli (no relation to composer Arcangelo or novelist Marie), who believe that life on earth was created as a laboratory experiment by beings from a planet “in our galaxy but not in our solar system.” According to the Buzz, the Miami chapter (fifty strong) was hosting a group of their Canadian cousins, and all of the assembled Corellians would be meditating daily on the beach. Sheila went off to meet her friends and resume the quest for the perfect crab cake, but I did not go with her, because I was curious about these Corellians. I wanted to infiltrate their number and observe them to see if I could find out why they believe what the Buzz said they believe.

The people closest to me, right beside me, almost too close for comfort, were passing the time smoking and glaring at one another, which might count as meditating. Are they Corellians? I wondered. I decided on the direct course of investigation; I would ask them.

“Excuse me,” I said. “May I ask you a question?” I presented my card.

They examined it closely, first turning it this way and that, apparently to confirm beyond doubt their original impression that it was a card, and then reading the name and job description in an accent that led me to ask, “Are you German?”

“Yes, we are German,” said the young son, who may have been repeating a memorized lesson. “We are a family on vacation. We are here to ‘soak up the sun.’”

The daughter, who was soaking up the sun in an attractive, even provocative, manner, flashed her eyes at me, smiled, and displayed her tongue stud.

“Explain this, please,” said the father, showing me my own card.

“Ich bin ein leidenschaftlich Zuschauer,” I said, “if I remember my high-school German correctly.”

“Ein Spion?” asked the boy eagerly.

“No, no, not a spy, just an idle watcher.”

The father of the group glanced uneasily at his wife and daughter, then fixed me with the stare of one who would like to have me clapped in irons.

“Well?” he said, in a tone that impugned my motives.

“Well,” I said, defiantly, “may I just ask you one question?”

“You have already asked us a question,” said the boy. “You asked, ‘Are you German?’”

“Ah! You’re right,” said I. “Sharp lad.”

“What is the question?” asked the father, clearly eager to have me ask it and then get on with the forced march to the dungeon and the rack.

“Are you Corellians?”

“No!” boomed the father. “We have already told you that we are Germans.”

“Let me put that another way,” I said. “Do you think that life on earth was created by aliens as a laboratory experiment?”

The father’s eyes popped. “Sir,” he said, with ominous calm, “I ask you to take your passionate spectacles elsewhere and leave us alone.”

“Yes. Certainly. Of course,” I said, and retired to my chaise.

In a moment, the boy’s shadow fell across my eyes. I looked up to find him holding my card.

“May I ask you, sir,” the boy said, turning the card toward me so that I could read it, exactly as his father had, but without the threatening note, “does one have to go to university for this?”

“Well, I did,” I said, “but it isn’t necessary. You can just go to SpeeDee Print on Collins Avenue and get some cards printed.”

“I think that I would like — ” the boy began, but a mighty roar of unmuffled engines overwhelmed and distracted him. Two young men on personal watercraft had come flying up out of nowhere on their way to some other nowhere and were now buzzing in circles, making waves and noise, apparently uncertain about where the way to nowhere lay. “My sister and I would like to pilot powerful personal watercraft,” the boy shouted, “like those fortunate bastards out there,” he added, tilting his head in the direction of the water, “but,” with a curl of the lip, “Father considers them a frivolous waste of money and gasoline, so we are condemned to sit here and bake in the sun like plums becoming prunes.”

“I dislike prunes,” I remarked.

“I dislike prunes very much,” said the boy.

Our attention was diverted by an enormous woman who arrived just then and spread on the sand a towel too small to hold her. She was wearing a black one-piece bathing suit but immediately rolled it from the top down, reducing the top to a black hoop around her hips and revealing great spheroid masses of herself. She then tried to loll. In the attempt, she twisted, turned, grimaced, and grunted.

The boy and I observed her in silence for some time.

Failing to find a position that would fit all of her onto the towel, she at last gave up lolling and began to read instead. She had brought with her in a large canvas bag a thick paperback book, well worn, called The Vampire’s Vacation.

“You have the card,” I said to the lad. “Why don’t you ask her?”

“If she’s German?”

“No. If she’s a Corellian.”

“Oh, yes. The alien experimentations.”

He walked over to her towel and said, “Excuse me, madam. May I present my card?”

She looked up at him, shading her eyes with her hand, wrestled herself onto one elbow, extended a plump arm, and took the card. She read it. Her lips moved as she did. “Is this a magazine?” she asked. “Passionate Spectator?”

“No, it is the designation of one who stands just a bit to the side of life and watches it,” said the boy, doing quite a creditable job as an apprentice or squire.

“Interesting,” she claimed.

“And so I would like to ask you a question.”

“Yes, well, go ahead.”

“Are you a Corellian?”

She squinted at him and said, with a little laugh, “No, I’m Catholic. Why do you ask?”

“I was wondering whether you believed that humans were put here as part of a laboratory experiment.”

“I guess you could put it that way,” she said, with a fuller laugh. “I hadn’t thought of it like that, but I suppose that is what we believe. Eden, and all that.”

The boy didn’t know where to go from there. He turned and looked to Mentor for guidance. I waved him back to my side.

“A dead end, a dry well, a frozen waste,” I said. “Some avenues of inquiry will get you nowhere. However, here’s something interesting.” I handed him the binoculars. |

| |

Scroll down for another sample.

“Eric Kraft’s new novel is not only funny and smart but also as devious as a Möbius strip, turning in on itself, doubling back through events that have already occurred, and generally subverting our Newtonian world view.”

David Kirby, St. Petersburg Times

Another Sample

WHEN WE WERE OUTSIDE, walking along Ocean Drive, I said to the duke, “Just curious, your grace, but where are we going?”

“Where are we going?” said the duke. “Ho-ho-ho.”

“Ha-ha-ha,” said I, “but seriously, where are we going?”

“Well, we are proceeding to the unveiling of the Limo Fountain. And we have arrived,” said the duke.

In the plaza at the entrance to the hotel Shangri-La-La, klieg lights swept the sky, crisscrossing above a massive something draped in white fabric. Arranged along one side of the drapery was a crew of models and musclemen, ready to remove the wrap when the time came.

The duke and duchess took a long step up onto a platform, where they stood before microphones and television cameras.

“Good evening, everyone,” said the duke, in a voice so assured that it silenced the crowd at once. “If you listen to ‘Drivin’ with the Duke and Duchess’ on Smooth Radio 109, you already know us, of course. I am the duke and this is my duchess.”

“Howdy, y’all,” said the duchess.

“It is our very great pleasure to welcome you to the unveiling of the Limo Fountain and to introduce you to the woman of the hour, our dear friend Ivy, the artist known as I-V-Y.”

This occasioned laughter and applause. I joined in both.

Ivy blinked at her audience and said, “I’m amazed so many of you showed up.”

Nervous laughter, mingled with puzzled murmurs.

“I want to say something about my work,” she asserted. She cleared her throat and said, “‘Those who have no experience of wisdom and goodness, and are always engaged in feasting and similar pleasures, are brought down, it would seem, to a lower level, and there wander about all their lives.’”

“You got that right,” said the duke.

“‘They have never looked up toward the truth, nor risen higher, nor tasted of any pure and lasting pleasure. In the manner of cattle, they bend down with their gaze fixed always on the ground and on their feeding-places, grazing and fattening and copulating—’”

“Amen, sister,” shouted someone in the crowd.

“‘—and in their insatiable greed for these pleasures they kick and butt one another with horns and hoofs of iron and kill one another if their desires are not satisfied.’”

“‘Hoo!’” said the duke.

Ivy let a moment pass, then added, “Plato. The Republic. Pretty cool, huh? Prescient, right? . . . Right?”

“Right!” called a few voices from the crowd.

“What else?” She consulted her digital assistant. “Oh, yeah. I was going to say something about kitsch, because that’s the other thing my work is about. See, the essence of kitsch is motive. It’s the willingness to go for effect rather than truth. To move an audience rather than saying something. To appeal to the heart and not the head.”

“You’re losing them,” warned the duke.

“Oh, yeah. Hey, sorry I’m getting so technical here.”

“Why don’t you just let the work speak for itself?” said the duchess.

“I think I’ll just let the work speak for itself,” said Ivy. “Let the veil be rent asunder!”

“Ahh, in just a moment,” said the duke, rushing to interpose himself between Ivy and the microphones. “We’ll be rending the veil asunder in just a moment, but first I want to make sure everyone knows that immediately following the unveiling, reproductions of the Limo Fountain will go on sale in the boutique to my right.” He indicated a tent.

The duchess leaned closer to the microphone and called out, “Strapping lads, haul away!”

The oiled beefy boys hauled with choreographed effort and choral grunts, and the drapery began to slide along the hidden contours of the work beneath it, until it reached a critical point and slid with a sailcloth sigh to the plaza pavement. The fountain stood revealed.

It was a stretch limousine rampant, rearing as a steed does in an equestrian statue, its massive haunches flexed, hind tires compressed under the weight, its long back bent, its foretires pawing the air, its hood and front bumper drawn back liplike, its grill teeth bared. Mist sprayed from its radiator cap like steam from the nostrils of a straining steed. A kink in the exhaust made it resemble a stallion’s pizzle, and water arced in a fine stream from it. The limo was peopled with fat figures, made of stacks of balls, like bronze snowmen, leaning from windows and rising like prairie dogs from a multitude of openings in the roof: the driver leaning from his window, swatting the limo’s flank with his driver’s cap, urging it on; a drunken frat boy spewing bronze vomit down the side below one window; a bronze pop diva standing up through a sunroof, waving to her fans, one strap of her tiny dress fallen, revealing her right breast; a baseball player, a hockey player, and a hip-hop gangsta brandishing the tools of their trades: a bat, a stick, an automatic; a prom king tearing the wrapper from his queen; a developer, a potentate, a candidate, and a judge, stuffing bundles of bronze bucks into one another’s mouths; and below them, in the shadow of the limousine, a herd of indistinguishable little figures, of indeterminate sex, scrabbling for the bills and coins that were falling from the passengers’ hands and pockets and dribbling from the exhaust, where a bronze likeness of the artist herself squatted, smoothing with her bare bronze hands rough metal to shape the back bumper.

|

| |

“A personal journey that is mundane in detail yet mythic in scope. Less a narrative than a gamboling reflection on the ways in which memory shapes supposedly objective history. That the book also manages to entertain the neophyte is a credit to Kraft’s colorful, incisive prose and off-kilter wit.”

Steve Smith, Time Out New York

“Whatever he does as a novelist, Eric Kraft will always have my gratitude for one thing: creating what may be the happiest and least neurotic sex in American literature. At stake in Passionate Spectator is nothing less than an assessment of each person’s place in the universe—as a spectator who gives shape to life simply by watching and remembering.”

Jim Ridley, Nashville Scene

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

“There are few contemporary American works of fiction as humorously erudite or eccentrically ambitious as Eric Kraft’s cycle of novels, The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences and Observations of Peter Leroy.”

Michael Upchurch, Seattle Times

Read complete reviews.

|