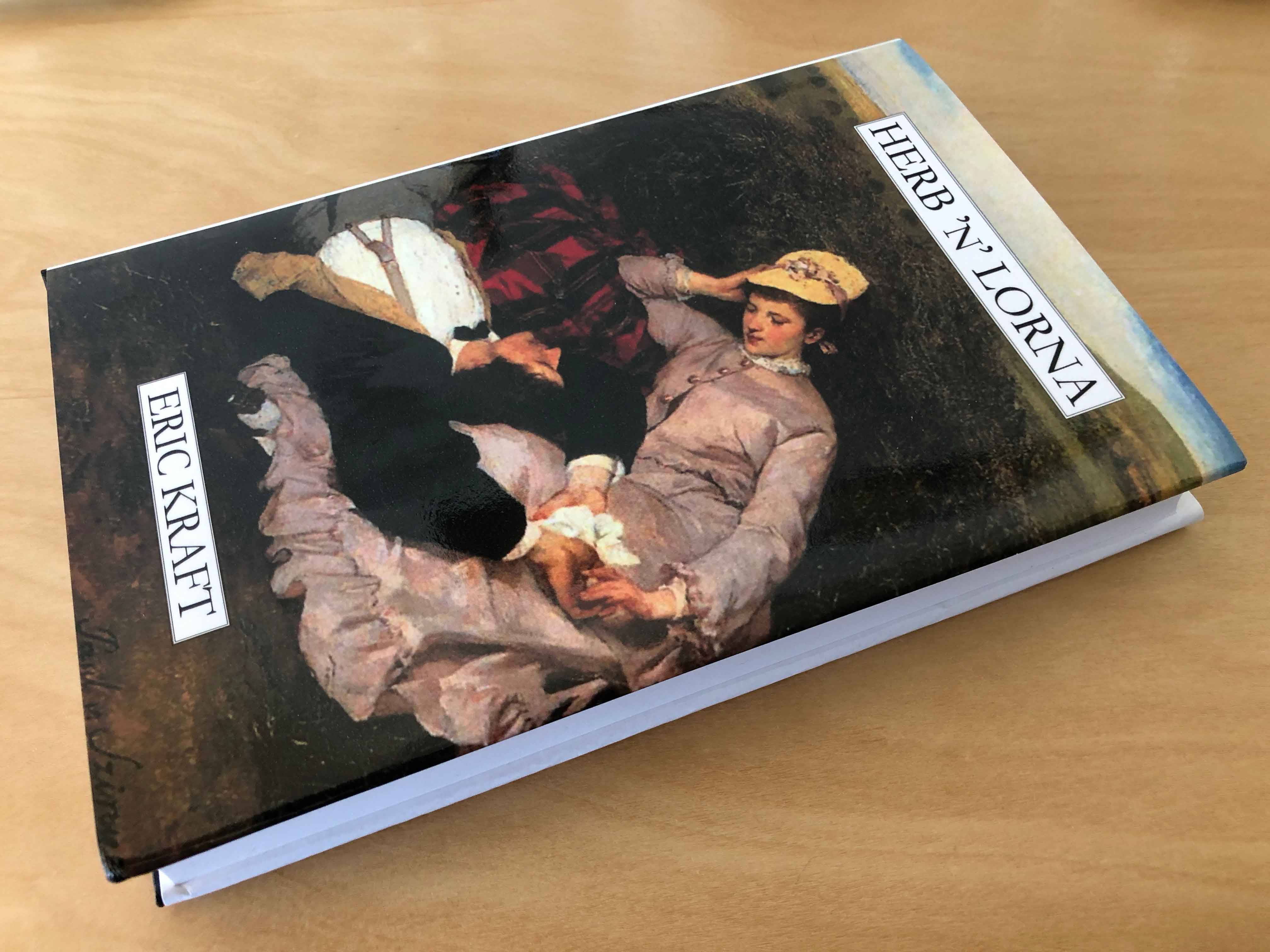

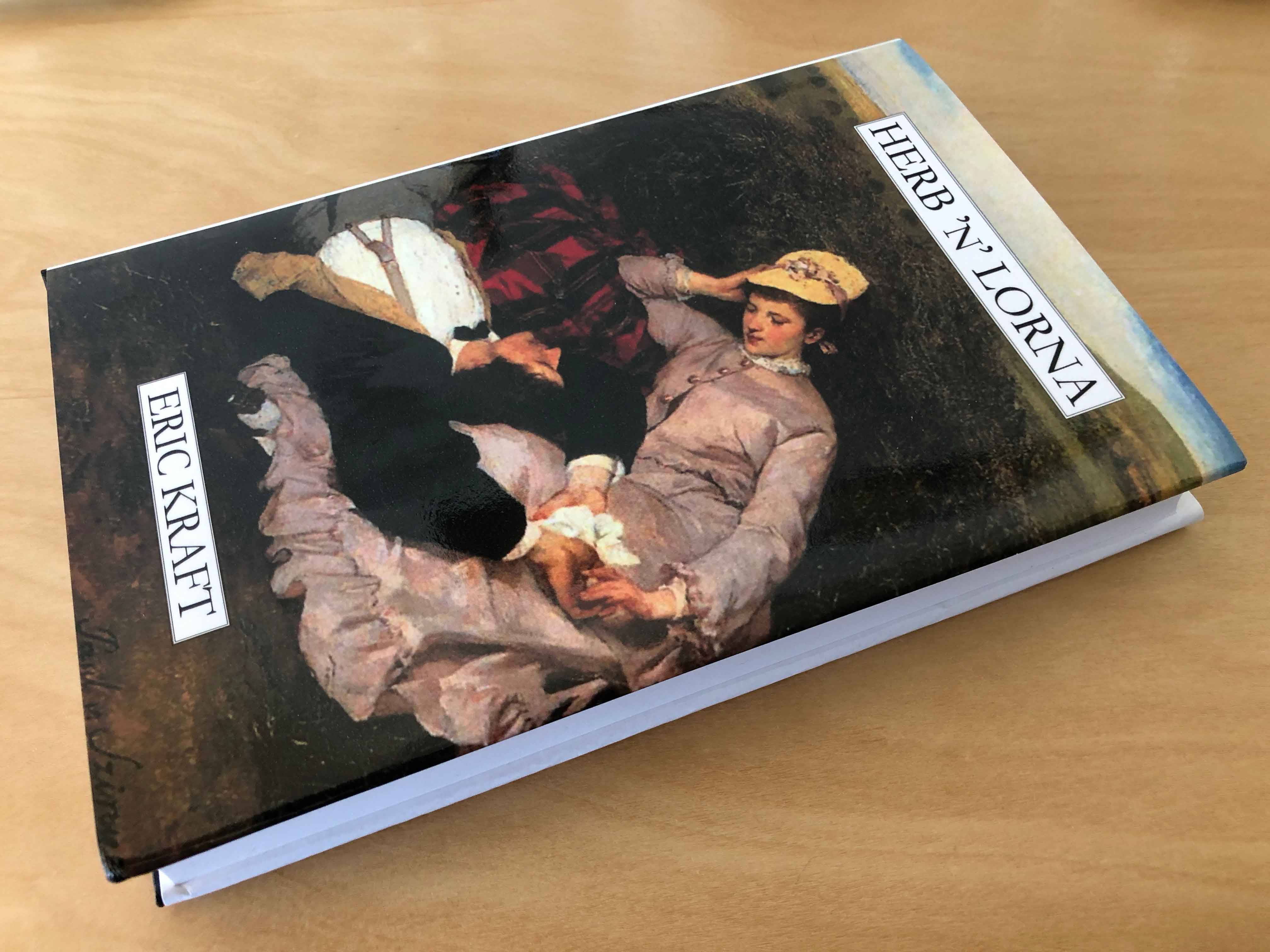

HERB ’N’ LORNA

(A Love Story)

By

ERIC KRAFT

“There aren’t enough adjectives to praise this delightfully generous storyteller. Herb ’n’ Lorna is a classic. Savor it.”

Andrei Codrescu, National Public Radio

Cover Image: Szinyei Merse, Lovers (detail, 1869)

“Eric Kraft’s Herb ’n’ Lorna is a historical farce, a comedy of four generations of happy errors. This very funny novel — as graceful, complicated and exhilarating as a quadrille — is an appreciation of folly, not a satire of it.”

Cathleen Schine, The New York Times Book Review (front page review)

On the surface, Herb and Lorna’s story seems like an American myth: small-town origins, Jazz Age romance, Depression trials, and postwar prosperity. By the 1950s, they seem to be a typically sunny American couple. Herb sells Studebakers to the citizens of Babbington, a Long Island seaside town, and Lorna is his cheerfully coy and clever wife. However, after Herb and Lorna have died, their grandson, Peter Leroy, discovers, “that my maternal grandparents were involved in—virtually the creators of—the animated erotic jewelry industry.”

“A beautiful book.”

Marc Munroe Dion, The Kansas City Star

A Sample

(from Chapter 5, In Which Herb and Lorna Meet but Are Separated by War)

WHILE BEN SPENT TIME in the Chacallit House dining room, drinking coffee, eating stew and sausages and potato salad, and chewing the fat, Herb sold Professor Clapp’s Five-Foot Shelf from door to door. It took Ben a day to establish himself as a pleasant fellow traveling with his nephew to teach the boy the book business, to help him find his feet. In the afternoon of the second day, a Chacallitan, Axel Schweib, shot his cuffs during a conversation with Ben, as if gesticulating to emphasize a point, displayed in so doing a really remarkable pair of erotic links, and then went on to deliver a pitch for Ben’s taking erotic links and studs on as a sure-to-be-profitable sideline. Ben expressed interest, with reservations. A meeting was arranged with Luther Huber for the next day.

In the meantime, Herb had found Chacallit fertile ground for book sales. So successful had he been that he kept selling nonstop, knowing that everything he made would buy more coarse goods. On the second evening, he worked right through dinner, stopping at houses along the road that wound upward from the town. Rain began to fall. He thought of quitting for the day, but he was doing so well that he said to himself, “I’ll make one more stop, at that house just ahead, the one with its windows glowing.”

It was the narrow house on Ackerman hill, where Lorna sat in the parlor with her parents.

THE MOMENT when Lorna opened the door was not one of those moments in which her elusive beauty shone, so Herb wasn’t dumbfounded at the sight of her. He didn’t stand there on the porch transfixed, with his hand to his hat, his mouth hanging open. It wasn’t love at first sight. When Lorna opened the door, Herb saw a young woman with a nice-enough figure, a pleasant smile, and dark hair. She looked to him like a good prospect for books. Lorna saw a neat young man with a salesman’s case. He looked to her like a good prospect for a little diversion on a rainy night.

“Good evening,” Herb said. He removed his hat and smiled.

Lorna put on a look of exaggerated surprise. “You must be fond of rain,” she said, “if you think this is a good evening.” She returned his smile. She was looking forward to watching this neat young man try to persuade her father to buy whatever he was selling.

“I guess you’re right,” said Herb. “Not only rain, but wind and cold, too.” He chuckled. He liked her. He liked the pert and sassy way she spoke to him. He put his hat back on, stood again as he’d been standing when she opened the door, took his hat off again as he’d taken it off before, gave a shiver, and said, frowning, “Nasty evening.”

“What are you selling?” Lorna asked. She leaned against the door frame, and that’s when it happened: her beauty shone, and it intoxicated Herb, befuddled and delighted him.

“What are you selling?” Lorna asked again.

Flabbergasted, Herb looked at his case. It was on the porch, at his feet. He remembered that he was selling something, and that he had samples of it in that case, but he couldn’t for the life of him remember what it was.

“I—you—you’re,” he said, and stopped. He couldn’t make himself say, “You’re beautiful,” and he felt foolish for having begun.

“Yes?” asked Lorna. She knew what had happened. She had seen it happen before. She always enjoyed it. She was enjoying this young man, too. She liked the way he looked. She suspected that he was as straightforward and friendly as he appeared, that he wasn’t just putting on a salesman’s front. She also liked the way she could rattle him with a quick question.

Herb stooped to open the case at his feet and find out what he was selling. With the act of stooping, when he was bent over, with his eyes off Lorna, his memory returned. He took a deep breath, got a grip on himself. He grasped the handle of the case, straightened up, and, to his surprise, laughed at himself for having been so rattled. He said, smiling broadly: “Books.” He risked looking at Lorna again. He was surprised, puzzled, disappointed, and—so unsettling had the experience been—a little relieved to find that the befuddling beauty he’d seen before had disappeared. Had he fooled himself into thinking he’d seen it? Had it been only a trick of the gray light, a soft shadow that fell on her face in a certain way that would never be duplicated?

“Do you have Ben-Hur?” asked Lorna. She’d been wanting to read Ben-Hur for some time. One of the girls at the mill had promised to trade her copy for Lorna’s copy of The Life Everlasting, but the girl was an extraordinarily slow reader, and Lorna had begun to despair of her ever finishing the book.

“Well, no,” said Herb. “I don’t think I do have that one.”

“I saw the moving picture,” said Lorna. “Did you?”

“No,” said Herb. “I—”

“Lorna,” my great-grandfather Huber called from the living room, “who is that you’re talking to?”

Lorna leaned toward Herb, put her hand on his arm, and dropped her voice. “What’s your name?” she asked. She was inviting him to join her in a conspiracy, a conspiracy of the young, of children against parents. Herb would have told her his name at once, but he saw again the beauty that he’d seen a moment earlier, and again he was befuddled by it.

Lorna poked him. “What does your mother say when she wants you to come to dinner?” she asked.

“She says, ‘Supper’s ready, Herb.’ ”

“That’s nice,” said Lorna. She smiled. “ ‘Supper’s ready, Herb.’ You know what?”

“What?” asked Herb.

“I’ll bet your name is Herb,” said Lorna.

“Yes,” said Herb. “Herb. Herb Piper.”

“It’s Herb Piper, Father,” called Lorna. She spoke as if Herb Piper were someone her father had known for years, perhaps a boy she had gone to school with, and so convincing was her tone that Richard Huber reacted as if Herb Piper’s being there were an expected occurrence.

“Well, tell him to come in, then,” he called. “And close that door. The damp air is getting into the house.”

“Goodness!” said Lorna. She looked this way and that in mock terror. “Hurry inside, Herb Piper,” she said, “before the damn bear gets you.” She took Herb’s hand and tugged at him. “And try to calm yourself,” she added, in a whisper. “You’re going to do a fine job. You mustn’t let yourself be so nervous. Is this your first try at selling books?”

“No,” said Herb, a little offended. “It certainly is not.”

Lorna gave him a doubtful look. “It’s no disgrace,” she said. “You have to start somewhere.” She liked his nervousness, and she liked his face, his open, no-tricks-up-my-sleeve face.

“I’m not pretending,” said Herb. He couldn’t help chuckling when he said it. “I really am experienced, and in fact I’m very good at selling books.” Lorna liked this too, this pride in his ability. She also liked the way that, for all his apparent seriousness, he seemed always to be laughing, chuckling, grinning. She couldn’t have known that he wasn’t ordinarily much of a laugher, chuckler, or grinner, that it was she who made him feel like chuckling.

Lorna took his hat and umbrella from him. “I can’t wait to see you sell some books to my father,” she said. She turned and led the way into the parlor. |

Scroll down for another sample.

“A funny, sexy story told with consummate skill.”

Malcolm Jones, Jr., The St. Petersburg Times

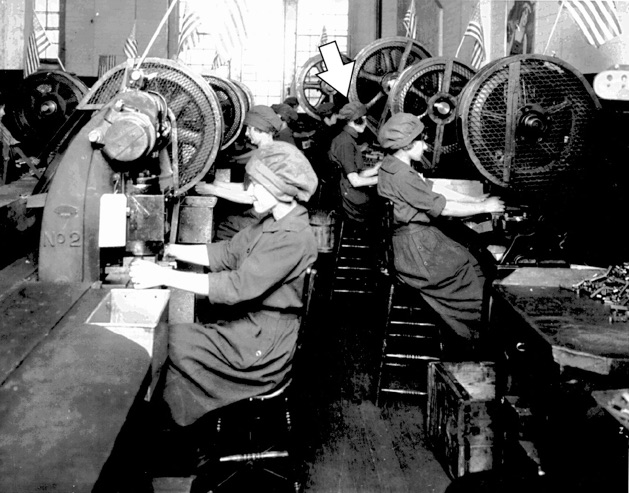

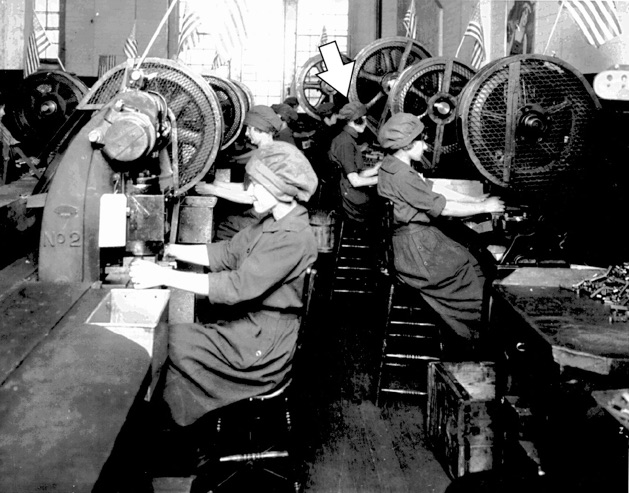

Lorna (arrow) working at a cutting machine on the main floor at Cole & Lord’s Gent’s Accessories, in Chacallit, about 1918. Note flags mounted atop machines at Luther Huber’s suggestion, to remind the women that belt buckles could win the war.

“It restores the blush of youth”

Barbara Holliday, The Detroit Free Press

Another Sample

(from Chapter 7, In Which Herb and Lorna Ignite the Flame of Passion)

BEN SAID SUDDENLY, “I’ve got a terrific idea! Not only is it a good idea, but it doesn’t take any of our money.”

“That sounds like a great idea,” said Herb. “What is it?”

Ben grinned and reached into his pocket. He brought out something that he quickly concealed with both hands. Then he held his hands out, one cupped over the other, hiding and protecting something precious, as he might have held a tiny bird. Slowly, he opened his hands. There, cupped in Ben’s hands, was the world’s first piece of animated coarse goods.

Herb burst out laughing. “Gosh!” he said. “Will you look at that workmanship!”

Ben’s prototype was a crude piece of work. The two wax figures were badly modeled, thickset, lumpy, graceless. The mechanism was nothing more than a pair of heavy wire forms joined by a loop and kept apart by a tiny coil spring. A crank turned a cam against the wire on which the man, the upper figure, was molded, and the action of the cam provided the jerky up-and-down motion that was all the animation of which the couple was capable. The act they performed was crude and basic.

“It needs work,” said Ben. “I know that. I don’t have the talent to do anything better than this. But you do. You do, Herb. You’re mechanically inclined. This kind of thing—much better than this, mind you, but this kind of thing—could be very successful, Herb. It could fit into a little case, like a pocket watch. It could go onto a chain just like a watch. Or it could take the place of a fob. Or maybe it would just be something a guy would carry in his pocket. The stem could make it work. You’d turn the stem instead of this crank, and—well, you see what I’m getting at, don’t you?”

“Yes,” said Herb, his mind already occupied with a set of interesting ideas prompted by the clumsy little couple. “I do.”

Ben’s idea was a good one, and Herb saw that it was. Animated coarse goods could sell for much higher prices, at a much greater margin of profit, than static carvings.

Herb worked night and day for a week to produce a more successful prototype, fabricated from two female figures that had been part of a shipment of conventional, static coarse goods from Chacallit. First, he had to make the tools his work would require. Then he had to transform one of the figures into a male. He wasn’t entirely pleased with the success of this operation, but he knew that he wasn’t likely to achieve anything better, so he went on to the articulation of the figures.

Painstakingly, he cut the figures apart at the elbow, shoulder, hip, and knee joints and across their abdomens, so that he could achieve more versatile and fluid movement than Ben’s figures had been able to manage. As far as it was possible to do so, he concealed the articulating mechanism within the figures, which required him to drill through the arms and legs and to carve cavities in the figures where his tiny wires, cables, and pulleys could be concealed. The challenge to his ingenuity was exhilarating, and Herb took great pleasure in the work. In a week, he had finished, and, on the whole, he was pleased. Ben was overjoyed.

“Brilliant work, Herb!” he said. “Brilliant! You’re a genius at this, my boy. You’ve got a great future! Collectors are going to be after these, and they’re going to want different positions, different ways of—well—moving, and so on. You’re going to be able to name your price. You’ve got talent, Herb, real talent.”

Herb shook his head. “No, Uncle Ben,” he said. “I did this for you, but I won’t do any more. I’m getting out of coarse goods. I’m in love with Lorna Huber. She’s a wonderful girl, and I’m sure she’d be ashamed of me if she knew about this.” . . .

LORNA WAS SURPRISED and suspicious when, on the day after her reunion with Herb, Luther asked her to come to his office at the mill, but her curiosity was aroused by Luther’s conciliatory attitude. She agreed to go because she wanted to find out what Luther wanted from her.

“Lorna!” said Luther, rising from his desk and rushing to greet her. “How are you?” He took her hands in his and looked her up and down. “No need to answer, my dear, I think you’ve never looked prettier. You’re glowing! Positively glowing.”

Lorna turned away. She knew that what Luther said was true, and she didn’t want him to begin speculating about why her cheeks had that rosy glow, why she was so quick to smile. She didn’t want him to have anything to do with Herb; if it could have been arranged, she would have kept him from knowing anything about Herb at all.

“It’s the springtime, Uncle Luther,” she said. She gave him a knowing look. “Surely you’ve noticed that girls glow in the spring.”

“So I have,” said Luther. He set his jaw and narrowed his eyes.

“Well, that’s enough of that, wouldn’t you say?” Lorna suggested.

“Yes,” said Luther. “That is enough of that. Sit down, Lorna. I want to show you something.” He waved her toward the leather wing chair in front of his desk. He settled himself in his own chair, paused for dramatic effect, and lifted the top from a small box on his blotter. From the box he produced Herb’s animated couple. He held the object out for Lorna to examine.

“Why, Uncle Luther!” she exclaimed.

“Spring seems to be advancing in your cheeks, Lorna,” said Luther. “We’ll be in high summer in a moment.”

“Who made this?” Lorna asked. She took the gadget from Luther.

“That’s not important,” he said. “Turn the little wheel at the side.”

Lorna gave the wheel a turn. “Oh, my,” she said. There was admiration in her voice, and Luther was encouraged. “Who carved these figures?” she asked.

“Originally? Gerald Hirsch, I’d say,” said Luther.

“You’re probably right,” said Lorna. “They look like his work. Who on earth performed the—ahhh, modifications?”

“To tell you the truth,” said Luther, “I don’t know. Nobody with any talent in that line.” He smiled and brought the tips of his thumbs and index fingers together. “Clumsy work,” he said, “but a brilliant idea, and a fine, fine job mechanically. Don’t you think so?”

“Yes,” she said. She twisted the wheel again, slowly, while she observed the little copulating couple from various angles. They enchanted her. In part, they won her over with their fluid agility and their cunning construction, but most of all, a small gesture won her: a gesture that Herb had supplied by shaping one tiny pulley with an eccentricity, the slightest little bump, like the lobe on a cam, so that at one point in the performance the man brushed his lips against the woman’s cheek. It was a tiny gesture, one that Lorna had to see several times before she could be sure that it wasn’t accidental, that it wasn’t caused by the way she held the figures or the way she turned the wheel. When she satisfied herself that it happened every time, with the precision of all the other gestures and exertions that composed the performance, when she was certain that it was intentional, that whoever had made the little couple perform had considered this sign of affection an essential part of the performance, she was charmed.

“Interested?” asked Luther.

Lorna looked at him, but a moment passed before what he had said registered. “In what?” she asked then, taken aback.

“In returning to carving,” Luther said. “None of the others could do this kind of thing the way it should be done. Trumbull, maybe. But not as well as you. Aren’t you intrigued? Think what you could do with movable joints. Imagine—”

“No, Uncle Luther,” said Lorna. “I’m through with all that. Forever.” |

“One of the undiscovered gems of recent American fiction: a romance of uncommon tenderness and complexity, a work of prodigious comic invention—and a damn sexy book.”

Jim Ridley, Nashville Scene

Herb (lower right) demonstrates the stability of the “Rigid Rockne” (even on three wheels!) to a skeptical customer outside Babbington Studebaker in the dispiriting days of 1933.

“A New York Times Notable Book of the Year (1988)”

“The novel is all about sex, and sex, in Herb ’n’ Lorna,means everything in life that is good — craft and art and imagination and hard work and humor and friendship and skill and curiosity and loyalty and love.”

Cathleen Schine, The New York Times Book Review (front page review)

(As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.)

“Wise and humorous, affectionate and witty.”

Publishers Weekly

Read complete reviews.

“Kraft es, en mi opinion, un maestro.”

Robert Saladrigas, La Vanguardia (Barcelona)

|